Does my UK Published Book Need an ISBN?

You might think the answer to this is a resounding yes, and in most cases it will be. In fact, technically the word “published” pretty much presumes you have an ISBN. However in some cases, the answer may surprise you.

Read on for more information.

As always, please note, this article is written in the UK for self-publishers who need a UK perspective on the subject. Readers in the USA or Australia may find the general information useful, but not the specific UK bits.

What is an ISBN?

An ISBN (International Standard Book Number) is like a birth certificate for a book. It means that the book is a recognised entity in the world. But if a human is born and, for whatever reason, does not have a birth certificate, then they are still a human being and every bit as real and legitimate as someone who does have one.

And just as a human needs a birth certificate, or some form of official recognition such as a naturalisation certificate, to participate in all aspects of society, so a book that wishes to be part of the big wide world of Goodreads, Amazon, Waterstones, and other major retailers, needs an ISBN

However, a book is still a valid thing – a product – which can, in certain circumstances, still be sold even without an ISBN.

When is it okay NOT to have an ISBN?

If your book will be sold exclusively by you; within your personal network, via your own website, at events and talks, or through third party selling sites like eBay, then is does not require an ISBN.

In addition, if you have a good friend or relative who owns a shop, and they have promised to stock your book, and they will buy copies direct from you, you do not need an ISBN. Even if the local bookshop wants copies and they are happy to buy them from you, then you probably don’t need an ISBN although the absence of an ISBN could really put them off.

When do I NEED an ISBN?

A barcode and ISBN on the back of the book makes it look more professional, so even if you think your local shop will buy direct from you, it might improve your chances if you have the ISBN.

You DO need an ISBN if you hope to see your book stocked in any book retailer that you can’t directly supply (and usually even if you can), or in any official organisation that sells books, e.g. the National Trust gift shops or any museum gift shop. These organisations will not (except in extremely rare circumstances) buy direct from the author. They also NEED a barcode in order to use their scanner at the point of sale.

N.B. – being ABLE to order your book does not mean that a particular shop will ever hold stock. That’s another big side issue.

You need an ISBN if you hope that your local library will buy a copy. Without an ISBN they simply can’t buy it at all. Also, without an ISBN you cannot claim any public lending rights royalties. (see below).

They may be persuaded to accept a donated copy, but you should check first because libraries do not usually accept unsolicited books to their collection. If your book has a lot of useful local content they are more likely to accept a copy and put it into the system. Even if you give them a copy, some libraries may still require a barcode, which realistically means you need an ISBN.

You also need an ISBN if you want to see your book listed on Goodreads, or to list it normally on Amazon. And, of course, if you are using any print-on-demand and distribution service, like Amazon KDP or IngramSpark then you can’t proceed without allocating an ISBN.

Amazon will, eventually, create a page for any book that has an ISBN. So will Goodreads.

You can add it yourself, or wait until it gets added, but it will be there when, or in case, anyone wants to review it or discuss it on Goodreads, or sell a second-hand copy on Amazon.

The Pros and Cons of an ISBN

Cons

- ISBNs cost money to purchase (quite a lot if you only buy one! See “How do I get an ISBN in the UK” – below)

- Once your book is published you have to give some to the legal deposit libraries.

- It’s a bit of extra hassle

Pros

- Your book looks official (because it is)

- Your book can (in theory) be stocked in bookshops

- Your book will (eventually) get listed on Goodreads and Amazon

That’s … more or less it, in a nutshell. I feel as though I have missed something here but I have to publish at some point.

How do I get an ISBN in the UK?

First of all, if you are self-publishing or being traditionally published with Blue Poppy Publishing then we handle all of this for you.

If you are self-publishing independently then you will need to purchase one or more ISBNs from Nielsen.

You can ONLY purchase UK IBSNs from Nielsen.

If anyone else offers to sell you an ISBN then your book will be officially published by them. The main exception of which I am aware is that Amazon KDP will offer you a free ISBN. While that technically means they are the the publisher of your book, it doesn’t mean a lot and you are still in control. However, if you are going to publish your book with a print run, or with IngramSpark either as well as, or instead of KDP then you need your own ISBN and you may as well apply it to KDP as well. (There is still some debate over this but it’s a side issue)

Here’s the link for the Nielsen ISBN store https://nielsenisbnstore.com/Home/Isbn

As soon as you go there you will note (at the time of posting) that the pricing system is just about the most unfair looking scheme ever.

- 1 x ISBN = £91

- 10 x ISBNs = £169 (or £16.90 each)

- 100 x ISBNs = £379 (£3.79 each)

- 1,000 x ISBNs = £979 (98pence each)

I expect there is a valid reason, but I can’t fathom it. Probably to do with processing fees. Heaven only knows how it works for Amazon, or Harper Collins who must use tens of thousands of ISBNs

Anyway, there’s nothing you can do about it, but do not be tempted to buy an ISBn from a company offering them to you for a tenner, or whatever. As I say, they will then officially be your publisher and you will almost certainly have difficulty listing your book properly on the database.

How do I get the book barcode for my ISBN?

Rule ONE: Don’t pay for this service.

The ISBN you get from Nielsen doesn’t come with a barcode. But you need one on your book. Luckily, there are plenty of websites that will make a barcode for you free of charge. My favourite one to use is BooksFactory who are a printer based in Poland. I love their quotes form, too, because it is instant and doesn’t require my email to get a quote. Also they are usually cheaper than everyone else’s, especially on very short runs.

Anyway, their barcode generator is here; https://booksfactory.co.uk/index.php?cPath=78_80

just copy and paste the number into the form and hit go. It will generate a B&W PDF of your barcode at the correct size – 25mm (1″) high – to insert into an InDesign or Photoshop (etc.) cover file.

Registering your book on the Nielsen database

This will need an article of its own at some point. If you want it and it’s not here then ask and I will try and motivate myself to write it.

In brief. Nielsen’s websites have terrible UI and I spend a lot of my life screaming at the screen. There are two main parts.

- https://www.nielsentitleeditor.com/titleeditor/ for adding new titles to the database

- https://bookorders.nielsenbooknet.com/ for informing you of any new orders from wholesalers.

Nielsen isn’t a wholesaler, they are a data service. You list your book/s on their Title Editor site with the correct ISBN, title, author name, cover, and all the other pertinent information and they serve it to the wholesaler which seems now to be just one comany, Gardners, who then provide that same data to the retailers, Waterstones and the rest.

If Waterstones want a book they place an order with Gardners who then send you and order through the Book Orders site. You raise an invoice and post the book to Gardners in Eastbourne, and they then open the package and add it to the order from the branch of Waterstones in your High Street. I know it seems crazy, but not as crazy as Waterstones ordering books from thousands of different athors.

Anyway, it’s a massive minefield and one of a number of good reasons to self-publish through a small independent publisher like Blue Poppy Publishing.

What is Legal Deposit?

As soon as you create a book-baby with its ISBN birth certificate you also have to give, free of charge, a copy of your book to the British Library. This is a legal requirement and you don’t get paid a penny for it. In fact you have to cover P&P as well.

Legal Deposit Office,

The British Library,

Boston Spa,

Wetherby,

West Yorkshire,

LS23 7BY

In addition they will probably ask you to send 5 copies to the other Legal Deposit Libraries. Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, Cambridge University and the Bodleian at Oxford.

If they ask, you are legally obliged to send them, but you don’t have to volunteer.

Agency for the Legal Deposit Libraries,

Unit 21 Marnin Way,

Edinburgh,

EH12 9GD

Again you can’t charge and you have to pay for postage. It is, however, worth using a signed for service. From personal experience, they haven’t always been 100% perfect in acknowledging receipt. Sorry to have to say that.

If you are using a Blue Poppy ISBN then this will all be handled at this end, and you don’t need to worry.

What about Public Lending Rights – PLR?

If your book is stocked in an offical UK library, and if even just one person borrows it, then you become entitled to PLR.

It’s not likely to be a fortune, possibly a few pence, perhaps a few pounds, but it’s every year, it’s free to sign up and if you don’t then you don’t get anything.

This is another area that could do with expanding into more detail but if you visit https://www.bl.uk/plr you can find more information. If you already have a book in print with an ISBN of course, then you should register, and claim your title.

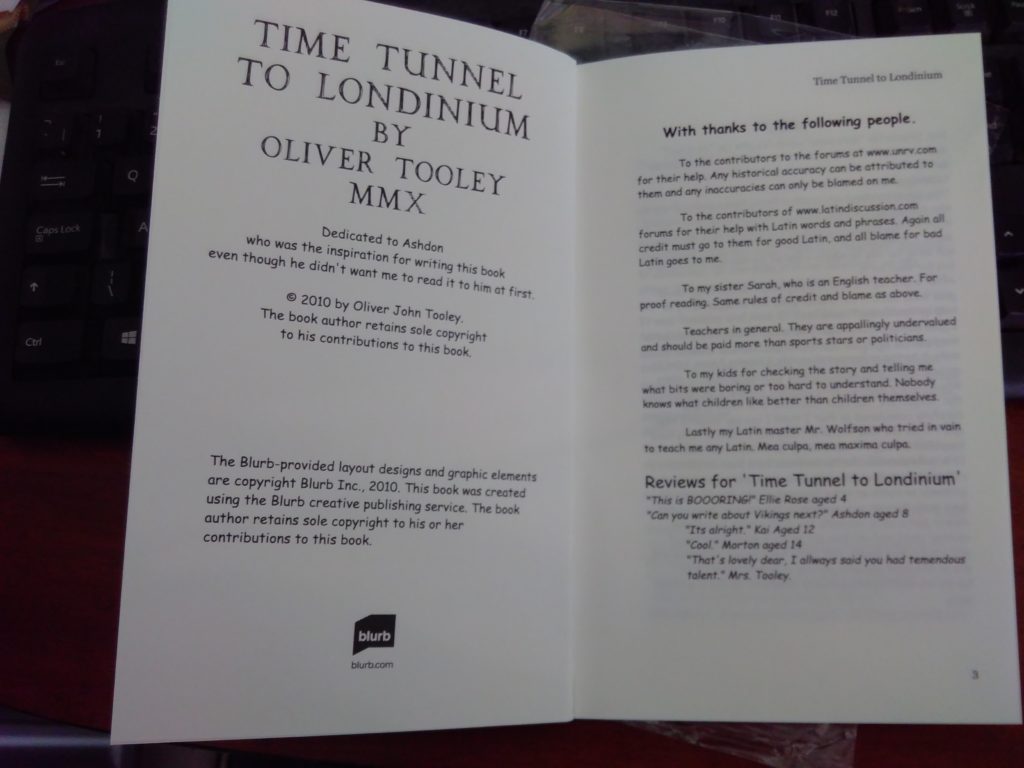

Let’s start with the front cover. Well ok, it could have been worse, but I mocked it up using images from the internet without bothering to check if they were available for reuse. (This is a serious mistake and nobody should ever do this, although I fear huge numbers of people do) If you cannot find an image you like which is officially available for commercial reuse and modification then you should not touch it with a barge pole. Take a photograph yourself, get a photographer, or artist, or a professional cover designer to help you. Rather use a WYSIWYG cover designer like on Amazon Kindle than leave yourself open to a copyright suit in the future.

Let’s start with the front cover. Well ok, it could have been worse, but I mocked it up using images from the internet without bothering to check if they were available for reuse. (This is a serious mistake and nobody should ever do this, although I fear huge numbers of people do) If you cannot find an image you like which is officially available for commercial reuse and modification then you should not touch it with a barge pole. Take a photograph yourself, get a photographer, or artist, or a professional cover designer to help you. Rather use a WYSIWYG cover designer like on Amazon Kindle than leave yourself open to a copyright suit in the future.